IT’S ALL IN HERE

The Courtauld Institute of Art is an independent college of the University of London, was founded in 1932 and it is a world leading centre for the study of history of art, conservation and curating. The Courtauld performed at the highest level in the Research Excellence Framework. Across all UK institutions, it tied 1st for research environment. 89% of The Courtauld’s research was deemed world-leading or internationally excellent in terms of originality, significance and rigour. It is therefore with great honor and deep gratitude that we present this historical-artistic analysis of our project.

How is Alfredo Meschi and Massimo Giovannini’s iterative project ‘In the Blink of an Eye’ promoting total liberation?

By David Bruno

History of Art

Courtauld Institute of Art

Most of the objects that we surround ourselves with are often doomed to be overlooked because they are mainly taken into account for their utilitarian function, however, they may hide a significant expressive potential that can ignite when integrated into wider creative discourses.

The contemporary Tuscan artist Alfredo Meschi incorporated the cross, a seemingly irrelevant, everyday mark that we commonly use to check off a list, into his iterative project In The Blink of an Eye, as the political tool through which he can promote total liberation. He joined forces with the Trentino-South Tyrol photographer Massimo Giovannini to develop and record their first artistic program and the community that has been gradually building around this artistic work.

Total liberation can be conceived, as exhaustively pointed out by Environmental Studies ProfessorDavid Naguib Pellow, as ‘the ethic of justice and anti-oppression for people, nonhuman animals, and ecosystems; anarchism; anticapitalism; and an embrace of direct action tactics’.

This political creed eschews violence against every form of life, whether human or non-humananimal, aims at dismantling hierarchical structures born out of the systematic oppression of Black and Indigenous people of color, neurodivergent and disabled individuals as well as women andthe LGBTQIA+ community. In fact, such principle envisages an intersectional framework, namely the interconnectedness of social struggles into a comprehensive effort against systems of power.

It also involves an environmentally conscious approach that rejects the consumption and exploitation of non-human beings and proposes an alternative system to consumerism, wherenatural resources are carefully managed to satisfy necessities and the production of goods does not significantly pollute the planet.

A fundamental aspect of total liberation concerns the recognition of non-human animals as individuals who are entitled of the same rights as humans since their moral status is often forgotten or belittled in social discourses. Alfredo Meschi, drawing upon Adriano Fragano’sphilosophical treaty Antispeciest Manifesto, becomes a spokesperson for non-human animal rightsthrough the creation of In the Blink of Eye. Fragano points out that ‘Antispeciesm cannot be considered abolitionist (it does not ask institutions to change laws or regulations), but liberationist, i.e. it aims at the liberation of animal individuals in its broadest sense.’

The liberation of beings, in this way, entails the full autonomy of choice, the end of any political superstructure that can potentially undermine personal freedoms, and the control over one’s body.These concepts lie at the foundation of the project inasmuch as they provide the theoretical landmarks that inspired Alfredo Meschi to create an artistic work that could upset collective consciousness and raise awareness about total liberation, using non-human animals as bulwark of this campaign. His approach is also derivative of the techniques of Augusto Boal’s Image Theater,thanks to which he assimilated the specifics of non-verbal performances and led him to use thecross as a political symbol, relying on the interpretative potential of everyday objects just like the Brazilian playwright taught in his oeuvre Theater of the Oppressed.

This paper will in fact investigate how In the Blink of an Eye project is shaping a communal understanding of the necessity to deconstruct Western ideas of civilization and its anthropocentric, speciest nature. Meschi and Giovannini’s works will be analyzed in light of the wider theoretical frameworks of Adriano Fragano and Augusto Boal in order to understand how they relate to theachievement of total liberation.

The relationship between the cross and the elaborate artistic inquiry conducted by these Italian intellectuals resides in the associative value of this sign, one that vehemently emerges in their artistic manifesto.

‘Disease x. “With this term we want to represent the awareness that a serious international epidemic can be caused by a pathogen of which we currently do not know the ability to cause diseases.” Way back in 2018, the World Health Organization inserted for the first time with these words the reference to an “X Disease” in the list of potentially pandemic infectious diseases from which humanity could not defend itself.’

‘Two years later, starting in January 2020, it seemed that Coronavirus had given a name to the unknown x. This skin, this embalmed body, belonged to a contemporary artist, who in the midst of chaos and panic claimed that the real pandemic was the Anthropocene itself’.

According to Meschi, the cross embodies something that lies beyond the mysterious illness that haunts the scientific community. The recent pandemic caused by the Covid19 virus, initially consirdered as the ‘Disease X’, was the symptom of a much wider problem: the Anthropocene.This scientific concept asserts that we are currently living in an ‘unstable geophysical epoch in which humans have become the leading global force whose exploitative way of living is causing the progressive decay of the environment. In this sense, an apparently ordinary sign such as the x can acquire a deeper meaning, one that warns us of a disruptive infectious illness capable of self-sabotaging and annihilating any source of life: humanity itself. Meschi denounces how people have abdicated their personal responsibilities and polluted their surroundings to the point of getting intoxicated. His crosses are in the first place the symbols of the catastrophic consequences of human civilization and the pathological character of modern life, a cycle of endless consumption of goods and individuals that will eventually implode.

As a matter of fact, the manifesto identifies a widespread lack of awareness regarding each form of life, either human or non-human animal, that diminishes interconnectivity among species. In a further section of In the Blink of an Eye this notion becomes clearer through the artist’s words: ‘We live in a society that causes us severe episodes of amnesia. Our consciousness of injustice, compassion, empathy doesn’t flow smoothly as it should. That’s why I was looking for a way to keep my consciousness flow, to not forget, not even for a second. Every second counts because in this short amount of time 40,000 not human souls are killed just to satisfy our appetite. My aim was to freeze this second or, even better, keep it pulsing on my skin to be always aware.“X” is a plain sign, a plain mark, a neutral letter. It's the sign that we use on our “to do” list when we finish to do something, to count something, to kill “something”.’

Thus the crosses not only serve as a reminder of the devastating power of humanity but also of the lives that perished due to mankind’s bottomless appetite. They also draw the attention on the fact that, unlike human individuals, non-humans get easily forgotten because they belong to other species, they are not worthy of being remembered, and overall their lives can be simply ‘checked off’ the list of beings worthy of respect, life, and ability to choose independently.

In the artist’s view, the root cause that catalyzed the dawning of the Anthropocene resides in the mistreatment and abuse of non-human animals and natural environment in favor of personal gain. The symptoms of the collective disease of post-industrial societies are the unconsciousness that accompanies one’s actions and the apathy towards living entities. The fulfillment of one’s appetite with the flesh of non-human individuals is the result of the chain of commodification of their lives,the subsequent processing of their parts, and the ultimate amnesia that separates human’ssuperfluous experience of pleasure from carnage.

In order to promote total liberation, Alfredo Meschi firstly tattooed himself in 2016 with 40,000 black crosses (Fig. 1) as a way to express his dissent and turn his physical appearance into a performative piece of art, one that he self-defines as ‘artivist’. Artivism is indeed a new artistic language based on the recovery of artistic activity for the purpose of immediate social intervention.His crosses, in fact, generate visual disruption and shock to the viewer because they are meant to stimulate reflection, they aim at inciting people to understand why the artist has covered himself permanently with the same pattern and ultimately play an educative role in teaching the value of life for all individuals. His work also surpasses conventional actions of political activism, whichmainly happen in social spaces like squares or streets, because it is designed to become a fixed element in the environment: Meschi wears his personal values on the entire surface of his skin, converting his body into a non-verbal, socio-environmental manifesto. The crosses have a permanent aspect that outdo the transience nature of political performances and this allows the artist to become an enduring point of reference in the context of social change because time cannot undermine his work. Every x, apparently disguised by its plain outlook, conceals the moral imperative to remind ourselves how destructive humans are and how many lives perished due tocivilization’s greed. Such bold visual stratagem is the first creative attempt to shape collective consciousness as the viewer remains stunned in front of the artist’s body and feels compelled to investigate the meaning behind the artist’s appareance. The purpose of this encounter is to leadthe viewer to a sequence of self-questioning, introspective work, and confrontation with the theme of total liberation, one that inevitably emerges out of the discomfort evoked by Meschi’s artivist piece.

In order to fully grasp the complex visual vocabulary of the crosses, it is of paramount importance to understand the theoretical frameworks that provided key educational contents to the artists and subsequently shaped the formal qualities of their works. Paul Freire’s book Pedagogy of the Oppressed played a primary role in the development of Meschi’s artivist pieces and the promotion of total liberation, especially his concept of conscientização. The term refers to learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality. This process dwells at the center of a wider discourse regarding the creation of one’s consciousness and the ‘banking’ educational model that, according to Freire, we are all affected by. This concept entails an unbalanced power relation between a teacher or a leading figure, and the student, who is influenced by the imposing nature of the subject who forcefullydeposits his knowledge into the receiver’s mind and does not permit to be contradicted. As a result, the student is oppressed by this educational model and loses not only the ability to provide critical interpretation to what he perceives, he also succumbs to the power of the teacher who manipulates his consciousness according to his own rules. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed thus poses itself as an antidote to this philosophy, a humanist and libertarian pedagogy, with two distinct stages. In the first, the oppressed unveil the world of oppression and through the praxis commit themselves to its transformation. In the second stage, in which the reality of oppression has already been transformed, this pedagogy ceases to belong to the oppressed and becomes a pedagogy of all people in the process of permanent liberation.

Alfredo Meschi has indeed recognized that the ‘world of oppression’ was interconnected, meaning that every social struggle could be united under one, far-reaching movement that fights againstsystems of power. He then decided to transform the reality of his very body with the crosses in order to transform the space outside of him, hoping that this could become an instrument of education, a living pedagogy that could teach people how to get away from any form of oppression. The correct method to achieve this lies in dialogue and the conviction of the oppressed that they must fight for their liberation as the result of their own conscientização.

Alfredo Meschi is the living evidence of how praxis can be pursued, even through artistic means.His tattoed skin works as a conductor of consciousness and this dialogical approach allows thefight for total liberation to be spread and amplified through the viewer’s reaction to the artist’s work.The shock and confusion caused by Meschi’s body serve to attract people to investigate why he covered himself with the crosses. He wants to act on the consciousness of people by stimulating their curiosity to find out more, to be educated on something they might not be aware of yet, especially their sense of morality.

As a matter of fact, this intellectual also places himself outside of Hans Haacke’s theoretical framework of the ‘consciousness industry’, namely the influence of museums and galleries to shape collective ideas on moral matters. Cultural institutions can decide what is morally acceptable or not by allowing certain artists within very specific environments by showing their works: this would validate their position in the industry and above all the ideas they express.

The performative nature of Meschi’s tattoos breaks the site-specific relationship between artworks and exhibition spaces: his skin is the canvas on which he operates, therefore it does not need to be allowed within certain cultural environments. It simply exists independently of any social superstructure.

Thus, the ability to upset one’s consciousness resides in the mute dialogue between the living manifesto that Meschi wears and the chain of questions and reactions rising out of the observer’s mind, capable of shifting his/her perspective on the relationship between humans and non-human animals.

The strength of this dialogical approach resides in the ability of corporeal presence to create meanings and arise sensations without the constraints of speech. This technique is derivative of Augusto Boal’s Theater Image socio-political approach and subversive artistic philosophy.

The Brazilian playwright, drawing from Freire’s pedagogical essays, proposed a revolutionary alternative to the bourgeois idea of theater, one that imposes a stark separation between public and actors, in favor of a proletarian one, where people can become actively engaged in the making of the show, or better, in his words, spect-actors.

In his book Theater of the Oppressed, he developed a Marxist analysis of the theater according to which oppressed individuals could emancipate themselves by conquering the means of theatrical production.

‘The poetics of the oppressed is essentially the poetics of liberation: the spectator no longer delegates power to the characters either to think or to act in his place. The spectator frees himself; he thinks and acts for himself! Theatre is action! Perhaps the theatre is not revolutionary in itself; but have no doubts, it is a rehearsal of revolution!’.

This statement is evidence of how Boal conceived art: a pedagogical tool capable of awakening the oppressed’s consciousness. He also provided a plethora of techniques to stimulate self-reflection, action, and dialogue within the context of theatrical performances. Among these, Image Theater has been identified as ‘the analytical basis of Brazilian theatre director Augusto Boal’s system of the Theatre of the Oppressed’. This non-verbal approach stems from the awareness that using only the body and its corporeality provided an alternative to language, an unreliablesystem of communication that could cause ambiguities due to the ever-changing nature of dialects and their semiotics. As accurately described by David Grant, ‘Boal’s holistic approach challenges the conventional wisdom that treats verbal language as the sole medium for thought, collapsing the distinction between language and gesture and leading us towards an understanding of image-making and reading that is at least as much phenomenological as semiotic: hence the idea that we can ‘feel’ meaning.

Once a viewer is intrigued by the crosses and decides to actively look for meanings, for example by reading the artist’s interviews, checking his website, or participating in one of this performances, he can mature the ability to perceive the pain behind the crosses because his sight is ‘trained to recognize something beyond an ordinary object.

Indeed, Alfredo Meschi successfully incorporated these notions into his thought-provoking works, using the checkmark as a medium of conscientização and his body as a self-conscious spect-actor. The x embodies the antispeciest message of total liberation and reveals the oppressed condition of the individuals while the corporeal quality of his tattoed skin, its stillness and non-verbal performative nature, expresses the collective anguish of the non-human subjectivities that perished due to humanity’s lack of empathy and induced amnesia.

This elaborate visual language, initially defined as Project X, is the foundation of what later evolved into In the Blink of an Eye, the ongoing, iterative project developed by Alfredo Meschi and Massimo Giovannini in 2017. The format of the program consists of a series of carefully pondered steps which are outlined on the project’s website. ‘Each performance of the project In the Blink of an Eye is divided into 3 main stages: Alfredo drawing the x (from 1 to max 4), the tattoo artist turning it into a tattoo and Massimo’s photo shooting. Each participant will receive their portraits’ electronic file ready to be printed in high resolution, posted to them a few days after the event.Each tattoo artist, in addition to appearing on our social networks and in digital and paperpublications, becomes a local referent for people who later want to partake in the ‘In the Blink of an Eye’ community.’

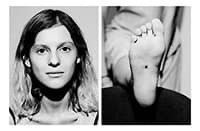

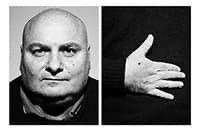

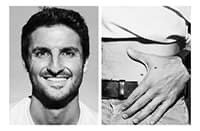

Participation to this artistic program is structured according to an equity principle as everyone is welcomed regardless of one’s appearance or personal ideas. Massimo Giovannini’s photographs, in fact, testify the universality of this project: young (Fig.2) and elderly people (Fig.3), male (Fig.4) and female partakers (Fig.5), known vegan activists (Fig.6) and even rabbit farmers (Fig.7); they all have a place within the group, however, the visual language of the photos virtually erases their differences in favor of the political message that they deliver.

These performative works can happen everywhere as long as there is a suitable location for tattooing and photographing. Most of the material is uploaded and advertised online because Internet is the fastest and most accessible tool to promote events to the widest audience possible.

Moreover, the formal qualities of the works, mainly light, and composition, mirror the social purpose of the project: promoting total liberation The sequence of dyptichs is intentionally designed to flatten out the figures of the participants, using a monochromatic filter that at the same time allows the overall rendering of works to be homogeneous and does not hide the characteristics of the people involved. This embodies the anti-civilization utopia of a society without hierarchical structures, a place where power is distributed equally among its inhabitants, both human and non-human animals. Giovannini conceives a startling visual vocabulary that plays with the interaction of two images in one cohesive format where the face of the individual , his most recognizable feature, is associated with the tattoo, the political device that holds a hidden antispeciest message (Fig. 2-7).

The treatment of the light stays the same throughout the entire length of the project in order to maintain consistency and avoid that one identity might prevail over the other, thus breaking the power balance within the group. The artist shoots with a 200W or slightly brighter 575W ARRI daylight lamphead, depending on the light of the ambience, and without diffusers, to create a more intense contrast in the photograph and to highlight the characteristics of the participants. Thischoice stems from the exigence to find a compromise between the specificity of the place where the artist works and the distance between the subject and the camera, roughly two meters, that might influence the intensity of the light and blur the physical features of the person portrayed.

The aspect ratio of a single photo is 4:3 vertically and it is implemented into the dyptich with a proportion of 6, 3:4 in order to respect the peculiarities of the individual who might have long hair, a particular imposing stance or not feel at ease in front of the camera. The possibility to play with proximity and distance allows the artist to fully frame the participant but keep uniformity as a guiding principle with minimum changes to the proportions of the works. The photographer also suggests the posture of the subjects, usually sitting with the elbows resting on the upper part of the legs and the face leaning forward, however, some people choose to sit straight as they do notfeel such a pose as natural. Giovannini combines all these diverse ways of sitting because they do not influence the formal qualities of the photos: the purpose of the works is to portray an aesthetically balanced representation of the community and primarily to catch the attention of the viewer through the magnetic force of people’s gazes.

As far as the tattoo section is concerned, the artist works without predetermined rules since the locations of the x’s, the kinds of clothes worn by the subjects, and generally their presence,necessitate adjustments that have to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. This project involvesa variegated corpus of corporealities, (Fig.8-9) facial expressions (Fig.10-11), and gestures(Fig.12-13-14) that mirror the multifaceted reality of humankind, one that wears its socio-political manifesto on the skin. The formal qualities of these shots, such as the homogeneity of the sources of light and the regularity of the format, imitate the linear, egalitarian organizational structure of an anti-speciest society where living entities can cherish their difference, be treated fairly, andpractice empathy on a communal level.

The theoretical grounds that guided this project, along with the aspiration towards a fully emancipated society, reside in Adriano Fragano’s philosophical inquiry on total liberation. The Italian intellectual, who played a major role in shaping Meschi and Giovannini’s works, wrote a manifesto that is also a strategic guide for a more ethical, utopian society where any form of oppression has been eradicated.

The purpose of his book is to propose a new relationship with animals based on an egalitarian concept and to break the ontological dichotomy of ‘Human-Animal’, strongly rooted in our culture,through theoretical tools

Such attitude is clearly mirrored by the ability of the two artists to grow a community based on these exact principles, where each participant is welcomed into the group and his/her individuality is genuinely respected. It is also conveyed by the formal qualities of the photographs whose uniformity aligns with the concepts of fairness and unity praised by Fragano.

The political message of In the Blink of an Eye benefits from the lucid analysis of the Antispeciest Manifesto inasmuch as the latter provides the terminology and the knowledge necessary to counteract the damages of the Anthropocene through a practical and theoretical way.

Firstly, the Italian author declares that ‘anthropocentrism is the ideology of domination that represents the foundations of modern human society. Therefore, those who are against it, aim at assuming attitudes and behaviors that can influence society and activating himself/herself through cultural, social, direct and personal initiatives for the creation of a new, more just, supportive, horizontal and compassionate human society: a free human society.’

Such ideas have incentivized the creation of a network of people that can actively partake in this transformation: each tattoed person can be identified not only as an activist but also as an agent of change, a transmitting device of consciousness that influences his/her surroundings through a cultural phenomenon, an authentic Freirian praxis.

Total liberation is indeed the primary purpose of the antispeciest fight and Meschi and Giovannini, along with their growing community, are pursuing this idea thanks to their iterative project, moving from one place to another and welcoming new individuals, who are willing to join their initiative and collaborate on the construction of a new society.

This program does not merely stimulate people to reconsider the relationship between humansand non-human animals, but it challenges every aspect of the interconnection among species. It galvanizes people to acknowledge the status of non-human animals as sentient beings, thus rejecting the self-proclaimed moral superiority that has historically induced humans to exploit otherforms of life. Such notion is widely discussed in the Manifesto where Fragano proposes a new series of responsible behaviors that aim at nullifying the pathological character of what Meschi calls ‘Disease x’. ‘He envisages 5 principles : self-defense, the possibility to perform an act of violence against an Animal as an extreme self-defense solution; proportionality, namely the relationship between the fundamental and non-fundamental interests of the subjects, where the indispensable procedures to maintain a subject alive and functioning are never overshadowed by their inessential counterpart; minimal damage, the principle according to which it is possible to take action to satisfy non-fundamental interests which are intrinsically compatible with the fundamental interest of others if the action involves the least possible impact; the principle of distributive justice, it entails that an action can prevail when it is evaluated as the most positive if its effects benefit the whole community of living beings and do no only satisfy the interests of one of the parties; and finally the principle of the restorative justice, the condition in which it is absolutely inevitable to cause harm to an individual (or group of individuals). It recognizes that theindividual (or group of individuals) is entitled to compensation that is as much as possible directlyproportional to the damage suffered.’

Such principles are key concepts for Meschi’s art: although they cannot be directly presumed by looking at the crosses only, they form part of the artist’s knowledge and pushed him to create the project. The participants, discussing with Meschi during the performances, will come across these notions as they provide a system of behaviours that can be put into practice when dealing with non-human animals. There is also an online space on In the Blink of Eye website where people can dialogue, look at the photos and share materials on the subject of total liberation.The multiple interviews and comments of both the participants and the artists themselves transmit a powerful sense of justice, fairness, and commitment to a communal cause but also leave room for self-reflection and personal interpretation. In a recently published article Alfredo Meschi firmly states how fixed labels such as vegan, anti-civilization, and anarchist do not necessarily provide a reliable system of categorization and risk delivering misleading interpretation of In the Blink of an Eye. Although these worldviews guarantee a theoretical framework that may guide a person intoidentifying what is acceptable or not, they also create ideological barriers that prevent newcomers from joining the community and primarily accept total liberation as a guiding principle. ‘Each and every one of us is dripping with contradictions. My art is not a purity contest. The freedom to express myself uncensored, from physical to ideological, is my antidote to hypocrisy.’ The living testimony of this statement is the Italian photographer Chiara Cunzolo, owner of Spazio Coworking, a cultural association based in Livorno. She has become part of the community, however, she claimed in the blog that ‘I am not vegan at present, but I believe that all of us, in order to do a deep work on our identity will have to welcome all ideas different from ours, sexual preferences different from our own, different lifestyle, different food choices ... All this can consolidate our identity or it can make us aware of the need for change. Welcoming is something more than sharing.’

This iterative work is indeed proof that cultural phenomena have the ability to gather a strikingly diverse human panorama that can work cooperatively on an alternative to the alienating, anthropocentric post-industrial society that haunts our present. It recognizes the need to explore our identities but also propels radical changes, such as the ones adopted by tattoo artist Michele Beretta. In the blog, he tells ‘Every X I tattooed on my client’s skin, transformed itself into the suffering of every individual creature I thought of. After a hundred Xs I felt my soul turning into iceand I started to tremble. I couldn’t finish the tattoo. After a fortnight I started again and in those Xs,this time around, I saw the animals that had survived by simply not eating them. From omnivorous I turned directly into vegan.’

As a result, the project places itself in an intermediate state, benefitting from the philosophical underpinnings of Fragano, Freire, and Boal, but also taking advantage of the possibilities of artistic creations and their inherent ambiguous, multifaceted nature. Massimo Giovannini and Alfredo Meschi’s works are increasingly gaining relevance within the artistic sphere thanks to the revolutionary message that silently shapes the consciousness of the individuals who seek freedom from the oppressed state in which they found themselves. In the Blink of an Eye is therefore notonly a sophisticated cultural experiment but also the commitment to awake empathy, to create ‘a sense of us’, a long-lasting feeling of togetherness among beings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beretta, Michele (15 June 2022). “From omnivorous I turned directly into vegan”. The Blog in https://www.intheblink.org/

Boal, Augusto (1974). “Conclusion. Spectator: a bad word”. Theater of the Oppressed (1974)

Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1989) . “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politcs, (University of Chicago Legal Forum,1989),(1)

Cunzolo, Chiara (22 June 2022). “Welcoming is something more than sharing”. The Blog in https://www.intheblink.org/

Exposito, Marcelo (2013). ‘La potencia de la cooperación. Diez tesis sobre el arte politizado en la nueva onda global de movimientos’. (Barcelona: MACBA)

Fragano, Adriano (2022). Manifesto Antispecista. Teoria, strategia, etica e utopia per una nuova società libera. Ed. 15. Veganzetta

Freire, Paulo (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Grant, David (2017). “Feeling for meaning: the making and understanding of Image Theatre.” The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance

Haacke, Hans (1996). “Museum, Managers of Consciousness”, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: a sourcebook of artist’s writings. Ed. Peter Howard Selz and Kristine Stiles. Berkeley: University of California Press

J. Perry, Adam (2012). “A Silent Revolution: ‘Image Theatre’ as a System of Decolonisation.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 17 (1)

Pellow, D. Naguid (2014). “Justice for the Earth and All Its Animals.” In Total Liberation: The Power and Promise of Animal Rights and the Radical Earth Movement, (University of Minnesota Press)

Meschi, Alfredo (2017). Manifesto in https://www.intheblink.org/

Steffen, W., Crutzen, Paul J., and McNeill, John R. (2007). "The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature," AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment , 36(8)

World Health Organization (2018). Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts in https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts

Photo of The Courtauld Institute of Art by R Boed, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1 Massimo Giovannini, Photograph of Alfredo Meschi for Project X, 2016

Fig. 2 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a young participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 3 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of an elderly participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 4 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a male participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 5 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a female participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 6 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of the popular vegan activist Alice Olivari of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig.7 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a rabbit farmer of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig.8 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a curvy male participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig.9 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a petite female participant of In the Blink of an Eye, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig.10 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a male participant of In the Blink of an Eye with a smiling face, 2022,11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 11 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a male participant of In the Blink of an Eye with a serious expression, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 12 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a male participant of In the Blink of an Eye covering his eyes with the hands, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 13 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a female participant of In the Blink of Eye showing her middle finger, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format

Fig. 14 Massimo Giovannini, Diptych of a female participant of In the Blink of an Eye posing naked, 2022, 11000x8000 px, ARRI daylight 575 with 6, 3:4 proportion on a .IIQ format